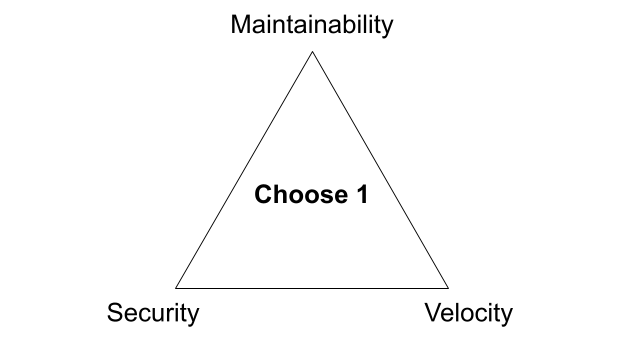

Security, Maintainability, Velocity: Choose One

There are three competing priorities that companies have as it relates to software development: security, maintainability, and velocity. I’ll elaborate on what I mean by each of these in just a bit. When I originally started thinking about this, I thought of it in the context of the “good, fast, cheap: choose two” project management triangle. But after thinking about it for more than a couple minutes, and as I related it to my own experience and observations at other companies, I realized that in practice it’s much worse. For most organizations building software, it’s more like security, maintainability, velocity: choose one.

Of course, most organizations are not explicitly making these trade-offs. Instead, the internal preferences and culture of the company reveal them. I believe many organizations, consciously or not, accept this trade-off as an immovable constraint. More risk-averse groups might even welcome it. Though the triangle most often results in a “choose one” sort of compromise, it’s not some innate law. You can, in fact, have all three with a little bit of careful thought and consideration. And while reality is always more nuanced than what this simple triangle suggests, I find looking at the extremes helps to ground the conversation. It emphasizes the natural tension between these different concerns. Bringing that tension to the forefront allows us to be more intentional about how we manage it.

It wasn’t until recently that I distilled down these trade-offs and mapped them into the triangle shown above, but we’ve been helping clients navigate this exact set of competing priorities for over six years at Real Kinetic. We built Konfig as a direct response to this since it was such a common challenge for organizations. We’re excited to offer a solution which is the culmination of years of consulting and which allows organizations to no longer compromise, but first let’s explore the trade-offs I’m talking about.

Security

Companies, especially mid- to large- sized organizations, care a great deal about security (and rightfully so!). That’s not to say startups don’t care about it, but the stakes are just much higher for enterprises. They are terrified of being the next big name in the headlines after a major data breach or ransomware attack. I call this priority security for brevity, but it actually consists of two things which I think are closely aligned: security and governance.

Governance directly supports security in addition to a number of other concerns like reliability, risk management, and compliance. This is sometimes referred to as Governance, Risk, and Compliance or GRC. Enterprises need control over, and visibility into, all of the pieces that go into building and delivering software. This is where things like SDLC, separation of duties, and access management come into play. Startups may play it more fast and loose, but more mature organizations frequently have compliance or regulatory obligations like SOC 2 Type II, PCI DSS, FINRA, FedRAMP, and so forth. Even if they don’t have regulatory constraints, they usually have a reputation that needs to be protected, which typically means more rigid processes and internal controls. This is where things can go sideways for larger organizations as it usually leads to practices like change review boards, enterprise (ivory tower) architecture programs, and SAFe. Enterprises tend to be pretty good at governance, but it comes at a cost.

It should come as no surprise that security and governance are in conflict with speed, but they are often in contention with well-architected and maintainable systems as well. When organizations enforce strong governance and security practices, it can often lead to developers following bad practices. Let me give an example I have seen firsthand at an organization.

A company has been experiencing stability and reliability issues with its software systems. This has caused several high-profile, revenue-impacting outages which have gotten executives’ attention. The response is to implement a series of process improvements to effectively slow down the release of changes to production. This includes a change review board to sign-off on changes going to production and a production gating process which new workloads going to production must go through before they can be released. The hope is that these process changes will reduce defects and improve reliability of systems in production. At this point, we are wittingly trading off velocity.

What actually happened is that developers began batching up more and more changes to get through the change review board which resulted in “big bang” releases. This caused even more stability issues because now large sets of changes were being released which were increasingly complex, difficult to QA, and harder to troubleshoot. Rollbacks became difficult to impossible due to the size and complexity of releases, increasing the impact of defects. Release backlogs quickly grew, prompting developers to move on to more work rather than sit idle, which further compounded the issue and led to context switching. Decreasing the frequency of deployments only exacerbated these problems. Counterintuitively, slowing down actually increased risk.

To avoid the production gating process, developers began adding functionality to existing services which, architecturally speaking, should have gone into new services. Services became bloated grab bags of miscellaneous functionality since it was easier to piggyback features onto workloads already in production than it was to run the gauntlet of getting a new service to production. These processes were directly and unwittingly impacting system architecture and maintainability. In economics, this is called a “negative externality.” We may have security and governance, but we’ve traded off velocity and maintainability. Adding insult to injury, the processes were not even accomplishing the original goal of improving reliability, they were making it worse!

Maintainability

It’s critical that software systems are not just built to purpose, but also built to last. This means they need to be reliable, scalable, and evolvable. They need to be conducive to finding and correcting bugs. They need to support changing requirements such that new features and functionality can be delivered rapidly. They need to be efficient and cost effective. More generally, software needs to be built in a way that maximizes its useful life.

We simply call this priority maintainability. While it covers a lot, it can basically be summarized as: is the system architected and implemented well? Is it following best practices? Is there a lot of tech debt? How much thought and care has been put into design and implementation? Much of this comes down to gut feel, but an experienced engineer can usually intuit whether or not a system is maintainable pretty quickly. A good proxy can often be the change fail rate, mean time to recovery, and the lead time for implementing new features.

Maintainability’s benefits are more of a long tail. A maintainable system is easier to extend and add new features later, easier to identify and fix bugs, and generally experiences fewer defects. However, the cost for that speed is basically frontloaded. It usually means moving slower towards the beginning while reaping the rewards later. Conversely, it’s easy to go fast if you’re just hacking something together without much concern for maintainability, but you will likely pay the cost later. Companies can become crippled by tech debt and unmaintained legacy systems to the point of “bankruptcy” in which they are completely stuck. This usually leads to major refactors or rewrites which have their own set of problems.

Additionally, building systems that are both maintainable and secure can be surprisingly difficult, especially in more dynamic cloud environments. If you’ve ever dealt with IAM, for example, you know exactly what I mean. Scoping identities with the right roles or permissions, securely managing credentials and secrets, configuring resources correctly, ensuring proper data protections are in place, etc. Misconfigurations are frequently the cause of the major security breaches you see in the headlines. The unfortunate reality is security practices and tooling lag in the industry, and security is routinely treated as an afterthought. Often it’s a matter of “we’ll get it working and then we’ll come back later and fix up the security stuff,” but later never happens. Instead, an IAM principal is left with overly broad access or a resource is configured improperly. This becomes 10x worse when you are unfamiliar with the cloud, which is where many of our clients tend to find themselves.

Velocity

The last competing priority is simply speed to production or velocity. This one probably requires the least explanation, but it’s consistently the priority that is sacrificed the most. In fact, many organizations may even view it as the enemy of the first two priorities. They might equate moving fast with being reckless. Nonetheless, companies are feeling the pressure to deliver faster now more than ever, but it’s much more than just shipping quickly. It’s about developing the ability to adapt and respond to changing market conditions fast and fluidly. Big companies are constantly on the lookout for smaller, more nimble players who might disrupt their business. This is in part why more and more of these companies are prioritizing the move to cloud. The data center has long been their moat and castle as it relates to security and governance, however, and the cloud presents a new and serious risk for them in this space. As a result, velocity typically pays the price.

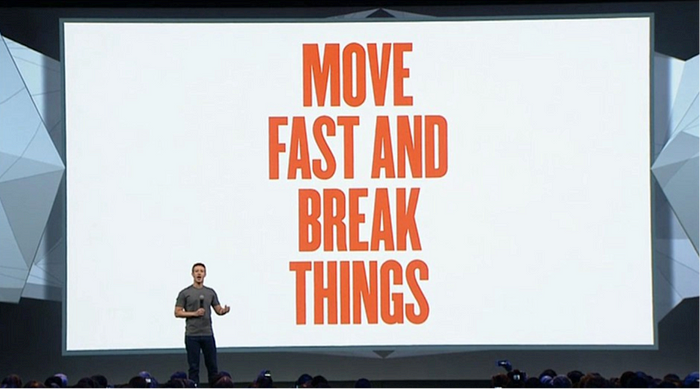

As I mentioned earlier, velocity is commonly in tension with maintainability as well, it’s usually just a matter of whether that premium is frontloaded or backloaded. More often than not, we can choose to move quickly up front but pay a penalty later on or vice versa. Truthfully though, if you’ve followed the DORA State of DevOps Reports, you know that a lot of companies neither frontload nor backload their velocity premium — they are just slow all around. These are usually more legacy-minded IT shops and organizations that treat software development as an IT cost center. These are also usually the groups that bias more towards security and governance, but they’re probably the most susceptible to disruption. “Move fast and break things” is not a phrase you will hear permeating these organizations, yet they all desire to modernize and accelerate. We regularly watch these companies’ teams spend months configuring infrastructure, and what they construct is often complex, fragile, and insecure.

Choose Three

Businesses today are demanding strong security and governance, well-structured and maintainable infrastructure, and faster speed to production. The reality, however, is that these three priorities are competing with each other, and companies often end up with one of the priorities dominating the others. If we can acknowledge these trade-offs, we can work to better understand and address them.

We built Konfig as a solution that tackles this head-on by providing an opinionated configuration of Google Cloud Platform and GitLab. Most organizations start from a position where they must assemble the building blocks in a way that allows them to deliver software effectively, but their own biases result in a solution that skews one way or the other. Konfig instead provides a turnkey experience that minimizes time-to-production, is secure by default, and has governance and best practices built in from the start. Rather than having to choose one of security, maintainability, and velocity, don’t compromise — have all three. In a follow-up post I’ll explain how Konfig addresses concerns like security and governance, infrastructure maintainability, and speed to production in a “by default” way. We’ll see how IAM can be securely managed for us, how we can enforce architecture standards and patterns, and how we can enable developers to ship production workloads quickly by providing autonomy with guardrails and stable infrastructure.